In 1959 Mattel Toys introduced a revolutionary new type of girl’s toy called “Barbie.” Although little more than a miniature plastic mannequin, unlike other dolls “Barbie” was unique in having a teenage lifelike figure and she soon became the clotheshorse for a limitless variety of outfits and accessories. Following her success a man in the licensing and merchandising business called Stan Weston came up with the notion of producing a similar toy, but for boys. Although he soon had Don Levine of Hassenfeld Brothers interested in the idea, there were still dissenters who deemed that a boy would never play with a doll. Nevertheless, the project went ahead and “G. I. Joe” was born. Released in 1964, it became an outstanding success and inevitably a number of other companies developed and introduced their own versions. Even following the release of the first Star Wars movie in 1977, after which fantasy toys began to replace those of reality, the movable figure concept still continued. Indeed, whether based on a motion picture or a comic-book character, many of these later-day superhero and humanoid playthings with their articulated limbs were still arguably the descendants of “G. I. Joe.” So much for the theory that a boy would never play with a doll.1

Yet rarely in the history of the toy fighting man has any concept been entirely new and throughout the ages boys have played with soldier dolls and American children were no exception. For instance, after the Confederate batteries had fired on Fort Sumter on April 12th, 1861, evidence tends to indicate that dolls dressed in military attire became quite popular playthings. It could be argued that they were the Civil War equivalents of “G. I. Joe.” However, it should be stressed that dolls during the period, unlike more modern times, usually had adult-like features, thus many a soldier doll of the 1860s did slightly resemble an “action figure” of much later years. Although it is impossible to say with any certainty, and while there were numerous commercial doll manufacturers in the United States, many if not most of the uniforms for soldier dolls were probably turned out at home. In fact, even the component parts that were required to make complete dolls were available to buy from fancy goods stores. Besides selling ready made toys, including dolls dresses and maybe a few “professionally” turned out soldier doll uniforms, these shops also sold such objects as doll heads, torsos and limbs. No doubt some soldier dolls also came about merely by giving an existing figurine a homemade military outfit. In fact, during the war soldier dolls may have been more prevalent than “pewter” toy soldiers, which due to their cost were often the reserve of the more wealthy middle and upper classes. In contrast, mothers of less affluent families, particularly those in rural areas, could quite easily have knocked-up a soldier doll of some sort, if only of the rag variety. No doubt, this was especially true in the Confederacy due to the Federal blockade of its ports.

While women and girls on the home front probably made the most soldier dolls, even some troops serving in the field turned their attention toward making them in their spare time. Besides whittling away at carving trinkets and small toys from lead Minie balls, it seems that another of their pastimes was fashioning “clothespin soldiers.” It has been said that the practice was particularly prevalent among wounded combatants who were recuperating in hospital. Apparently these convalescing soldiers often referred to their little creations as “clothespin penny dolls,” and sold them and the money so received was an extra source of income. No doubt some troops used pieces of uniform cloth or maybe even flags to clothe their small wooden figures and those shown in Illus. 1 and 2 are a fine

example. Dressed in what seems to be oriental style garb, this item was most likely intended to represent a Zouave.2 Of course, other men who had time to spare were prisoners-of-war and evidence suggests that some of these were not averse to making similar objects. Occasionally such a figure with

a known provenance does surface, such as the “Confederate soldier doll” that came up for sale at an antiques show in Richmond, Virginia, in April 1969. It was reported as having been “made by a Southern prisoner in the War Between the States.”3

However, whether made by a combatant, a professional toy maker, or a loving mother or child, like so many other Civil War era playthings, original source material referring to soldier dolls is almost non-existent. Occasionally they are briefly mentioned in diaries and memoirs, but only in passing. One person who slightly touched upon the subject was Margaret Junkin Preston of Virginia who wrote in her diary on January 9, 1862, about the influence the war was having on her children’s play. She said that five-year-old George, among other things; “administers pills to his rag-boy-babies, who are laid up in bed as sick and wounded soldiers.”4 However, whether young George’s “rag-boy-babies” were in some form of military attire is impossible to say.

was worn by my father during the Civil War in many parades for men leaving and returning

from battle.” The label also bears a signature which sadly is ineligible. By courtesy of

secondhandcollectibles (eBay Trader).

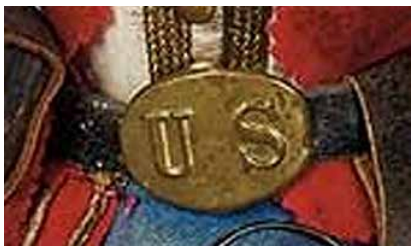

affixes the jacket’s toggle. It is of the pattern

commonly found on United States Army

enlisted clothing of the period.

What little evidence is available tends to indicate that the most favored costume for a soldier doll was that of the Zouave, a form of garb popularized by the French military following its conquest of Algeria. The first widely publicized American Zouave unit was formed in 1859. Called the United States Zouave Cadets and of company strength, it was commanded by Elmer E. Ellsworth.5 During the Civil War dozens of Zouave units were organized and their appearance was to have a profound impact on many children. Indeed, following the outbreak of hostilities it became quite fashionable to dress young boys in military uniforms and undoubtedly the most voguish was that of the Zouave – Illus. 3 and 4. Something which was touched upon by The Daily Ohio Statesman on October 10th, 1861, when it reported: “The Zouave dress, particularly, is very popular, we often see boys just large enough to wear pantaloons, rigged out in this style, and with wooden gun and toy knapsack complete.”6 Little wonder that Zouave dolls were favorite and that shown in Illus. 8 is a superb example. Of 1860s vintage, the doll is said to be of German manufacture. Note its diminutive gilt “US” belt plate. This small toy-like insignia was probably produced commercially because identical pieces have also been seen decorating other figures – Illus. 16.

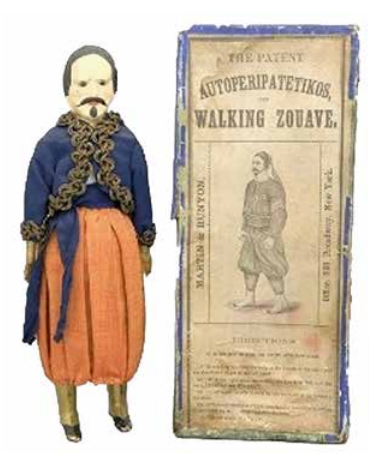

Arguably the most novel of the Zouave toys took the form of an automaton. Called “THE PATENT AUTOPERIPATETIKOS, OR WALKING ZOUAVE” and powered by a clockwork mechanism designed by Enoch Rice Morrison, this mechanical figure, which measured roughly eleven inches high, was probably made by Martin & Runyon of New York City from around 1863 through to about the late 1860s. Nevertheless, although rather expensive, costing roughly two dollars depending on the retailer, its uniform was still made of rather cheap commercial material. Its trimmed jacket was of dark blue cotton. A wide sash of the same lightweight material was tied around its waist and over a white cotton vest. Its cotton baggy red Zouave trousers were gathered as a single unit and not divided so as to prevent interference with the walking movement. The doll’s only underwear was a white cotton covering glued to its cylindrical body. Surviving examples indicate that the heels and toes of their brass feet were painted black. – Illus. 9.7

wearing a Zouave style outfit. The card bears the back-mark of F. Gutekunst, 704 & 706, Arch Street, Philadelphia. Writer’s Collection.

influence children’s everyday clothing as

indicated by this carte-de-visite of a boy

wearing a superb Zouave style “civilian” suit. The card bears the back-mark of Bogardus, Photographer, 363 Broadway, New York. Writer’s Collection.

Nevertheless, it seems that this was not the only commercially produced Zouave toy that was turned out in New York City during the Civil War years. Yet another type was the “JAPANESE ZOUAVE ELASTIC DOLL”, which was available at room number 17, 197 Bowery. Why “Japanese” is not known, but press advertisements tend to indicate that this type of plaything probably first appeared on the market in early 1865.8 Whether this particular version was imported from abroad or made in the metropolis is not clear, but undoubtedly some “Elastic Zouaves” were manufactured in New York.

Evidently they were turned out at the Elastic Zouave Doll Manufactory at 163 Mulberry Street. Although it was said that this company was “doing a good business,” in July 1865, its stock, fixtures and tools still came up for sale.9 However, it seems that this did not spell the end of the availability of

“Elastic Zouaves” in the city because in November 1867, it was reported: “A number of men in town are engaged in the laudable occupation of selling Zouave dolls and other toys, which hang suspended by an elastic string, and dance up and down ten hours a day for the edification of big-eyed babies.”10 Undoubtedly this must have been a very popular toy because in 1866 its play value was even touched upon in the Scientific American, which said in part: “The dervishes and zouaves fantastically dressed, suspended by an elastic cord, perform feats of leaping which put to shame the Buislays and Hanlons.”11 However, it was not only the children of New York City who had the opportunity to amuse themselves with this form of plaything. For instance, in November 1865, a firm called M. Halle & Company in Cleveland, Ohio, was advertising “SOMETHING NEW” in the shape of “Elastic Zouaves.”12

In fact, probably the most well documented and famous of all Civil War toys took the form of a Zouave Doll. It was owned by Tad Lincoln, the youngest son of President Abraham Lincoln. Tad named his Zouave doll Jack, but it seems that Jack had a somewhat checkered military career. Tad and his White House playmates constantly court-martialed him for such offenses as sleeping at his post, desertion, and even for spying. The executioner was always Tad who used his toy cannon, which had been given to him around 1862 by Captain John A. Dahlgren, the chief of the Bureau of Ordnance at the Washington Navy Yard Illus. 10. Although Jack was put to death for his treacherous deeds, he was still buried with full military honors and this is where the troubles lay. The boys persisted in burying him among the newly planted rosebushes much to the consternation of Major Watt, the White House gardener. To get around the dilemma the gallant Major suggested that Jack should be pardoned, which Tad thought was an excellent idea. Although President Lincoln obliged and granted Jack a written pardon on official

stationery, it did not last because in less than a week Jack had once more been executed. This time he was hung from a tree. The last time Jack was seen was “on top of the cornice of one of the East Room

windows, where he had been tossed by one of the boys.”13 What Jack actually looked like we will

probably never know, but there was at least one other child who owned a Zouave doll who often frequented the monthly parties given by President Lincoln for “boys and girls in the White House…”

Her name was Eliza and her Zouave doll was described as having “red trousers, red tassled (sic) cap, blue coat and equipped true to life even to a knapsack.” In later years when entertaining visitors and reminiscing about the olden days, one of the mementos she would show her guests was her Zouave doll, by which time and due to play-wear it had lost its hands – Illus 11.14

Illus. 8. Measuring twenty inches high, this is a superb

example of a Zouave soldier doll. The doll is said to be

of circa 1860s German manufacture and has a porcelain

shoulder-head, muslin stitched-jointed body, and leather

arms. Its uniform consists of a light blue woolen kepi,

red/blue woolen jacket with feather-stitch detail, and red

woolen trousers. Its belt, which supports a cartridge box

and pistol and holster, is fastened by a gilt oval “US”

belt plate. No doubt this insignia was possibly produced

commercially because identical pieces have been noted

decorating other figures. By courtesy of Theriault’s

Antique Doll Auctions.

Illus 9. A patent Autoperipatetikos or Walking Zouave Doll with its original box. Powered by a clockwork mechanism designed by Enoch

Rice Morrison, this mechanical

figure, which measures roughly

eleven inches high, bears the name of Martin & Runyon of New York City on its box lid. By courtesy of LiveAuctioneers.

Illus. 10. Tad Lincoln’s possible toy cannon. Apparently the supposed history behind this piece as a plaything began in 1862 when President Lincoln wrote a note to Captain John A. Dahlgren, the chief of the Bureau of Ordnance at the Washington Navy Yard, asking him to let Tad “have a little gun that he can not hurt himself with.” Today this miniature weapon is in the possession of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, but undoubtedly it never began life as a toy. With its bronze smoothbore barrel, which is roughly twelve inches long with a three quarter inch bore, it probably began life as a scaled model of a Dahlgren Boat Howitzer, but of a design that was never put into production. However, there is even debate as to whether this was actually “the little gun” which was played with by Tad. One particular source states that it was purchased by the Lincoln Museum “at an auction in the 1950’s, with no documentation as to its provenance, other than perhaps an auction catalog description.” By Courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

Referring back to Jack, Tad Lincoln’s Zouave doll, it is believed it was given to him by The Metropolitan Fair, an event which had been held in New York City from April 4, through to April 23, 1864. This was one of just many such gatherings that were organized throughout the country to raise funds for

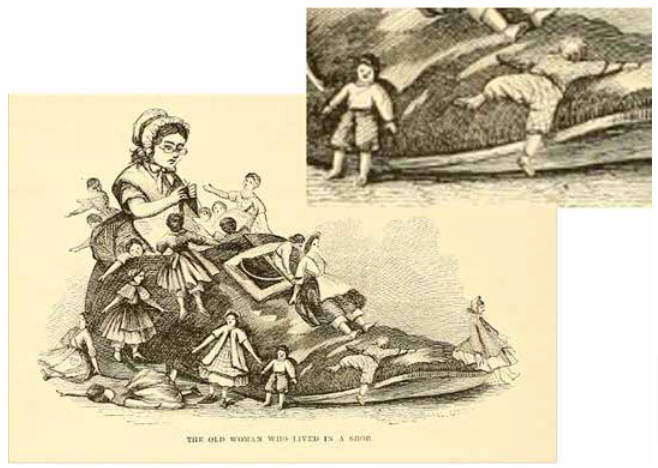

the United States Sanitary Commission. In effect, this organization was the Civil War equivalent of the latter day Red Cross. Besides displays of war relics and other attractions, these “Sanitary Fairs” always fostered numerous booths, some of which sold dolls and other toys. While most of the dolls were

probably of professional manufacture, no doubt their apparel, including soldier doll uniforms, was made at home by charitable ladies and girls who had given up their spare time – Illus. 12.15 The dolls

in question, no matter what type, often showed superb craftsmanship and were usually aimed at the more well-heeled of society. However, not all were directly sold to wealthy visitors, some were raffled, much to the advantage of the United States Sanitary Commission’s coffers.16

the nursery-rhyme character “the old woman who lived in a shoe.” Sitting in a giant shoe,

her children consisting of dolls that were for sale, two of which in this illustration seem to

be in the form of Zouaves. Woodcut from The Tribute Book: A Record of the Munificence,

Self-Sacrifice and Patriotism of The American People during the war for the Union, p. 194.

Before leaving the subject of Zouave soldier dolls, brief mention should also be made about their female equivalents, the vivandière figures, which were probably most popular with young girls. The origins of the true life cantinières and vivandières could be found in France. Indeed, since the French Revolution women had been seen on the battlefields administering refreshments and medical aid to combatants and although these females had become an accepted French military institution, it was not until the Crimean War when they gained worldwide attention.17 Thus it was inevitable that once the War Between the States had broken out some American Zouave commands would be accompanied by members of the fairer sex – Illus. 13.18 The vivandière dolls shown in Illus. 14, and 15 are in the form of sewing companions. The concept of the “sewing companion” doll was inspired by ladies magazines of the period which proposed that a favorite doll could be accessorized with sewing tools as though part of her costume.19

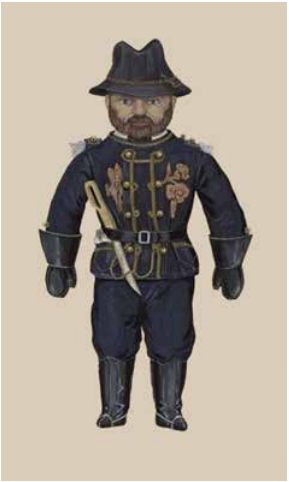

Although the rather flamboyant Zouave figurines were popular, numerous soldier dolls in more conventional looking uniforms were also evident – Illus. 17. Indeed, even the Index of American Design listed at least three examples. The Index of American Design was a Federal Art Project set up during the Great Depression as a work-relief program. Between the years 1935 and 1942, approximately four hundred artists were employed to create watercolor renderings of American folk and decorative art objects ranging from early colonial times through to around 1900.20 In the process numerous old toys were recorded, including the three Civil War era soldiers dolls shown in Illus. 18, 19 and 20.

Whether these three soldier dolls still exist the writer does not know, but undoubtedly similar pieces have survived the rigors of time and can occasionally be seen in toy collections today. However, being that many, if not most, were turned out at home and like all homemade toys they are rather difficult to authenticate and accurately date. Usually the collector has to use his or her own initiative to determine a homemade toy’s vintage and the two miniature garments shown in Illus. 21 and 22 fall into this category. So the story goes these two items were found in a box in the attic by a person upon inheriting his grandparents’ estate. Although his grandfather and grandmother had been antique collectors and were probably quite knowledgeable on the subject, he still decided to have them appraised by a Civil War militaria dealer who declared that they were of the 1861-1865 era. Both pieces were cut from the same dark blue cotton material and while they are large enough to have been worn by a very small child or a baby, they probably were intended for a soldier doll. Regarding the sack coat, sewn to the garment are four genuine United States Army cuff buttons – Illus. 23. However, they are not of the more common pattern usually seen on U.S. Quartermasters Department issued clothing (see Illus. 4), but

of a commercial type that could be privately purchased from military supply houses and similar outlets. While the design of this button’s shield is often associated with more modern times, the pattern was undoubtedly in use during the 1860s.21 As for the forage cap, the diminutive brass buttons that affix the chin strap are of a type which could be found on many items of doll’s apparel during the period. However, more interesting is the gilt embroidered number “101” that adorns the cap’s front – Illus. 24. No doubt, this number represented the regiment in which the child’s farther was serving. Only five states could boast of a regiment with such a high designation, they were Illinois, Indiana, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.22

has a bisque shoulder-head, muslin body,

and bisque lower limbs. Note its miniature

gilt oval “US” belt plate. By courtesy of

Theriault’s Antique Doll Auctions.

Of course, children in the South suffered far greater hardships than those in the North and due to the United States Navy’s blockade, even commercially made playthings became a rarity. With shortages becoming particularly noticeable at Christmas, some of the excuses given to youngsters for the absence of toys were that the blockade had held up Santa’s journey or prevented him from visiting. Nevertheless, if at all possible parents still endeavored to furnish their children with gifts at Yuletide, but increasingly items were being turned out at home. Eighteen-year-old Susan Bradford of Bradfordville, Florida, recalled how the making of toys taxed “the inventive powers to the utmost” and how she, her mother, and several aunts made presents for the young ones, including rag dolls some of which were dressed “in Confederate uniforms…”23

Nevertheless, some toys still managed to find their way past the Yankee blockading squadrons, but they were costly and usually the reserve of the more opulent planter class of southern society. For instance, in South Carolina it was said that affluent officers, away for long periods of time, sent home exquisite China dolls and other expensive toys that had slipped through the blockade.24 In January 1865, the ladies of Columbia, South Carolina, held a “great bazaar” in the State Legislature to raise funds for wounded soldiers and some of the luxury goods available had passed through the blockade. Referring to the cost of such items, seventeen year old Emma Florence LeConte recorded in her diary on January 18: “Some beautiful imported wax dolls, not more than twelve inches high, raffled for five hundred dollars, and one very large doll I heard was to raffle for two thousand.” Upon hearing this her uncle, Professor John LeConte who was the superintendent of the Nitre Bureau works in Columbia, remarked; “one could buy a live negro baby for that.”25 Of course, the prices being realized were in Confederate dollars; a currency which within a few months would be worthless.

American Design is this watercolor, graphite, and gouache on paper rendering by Verna Tallman, circa 1938. Listed as being ten and a half inches high, it seems little is known about this toy. Nevertheless, the artist’s impression of this piece suggests that it was of the knitted variety. As always, knitting was quite a common pastime for women and girls during the period. By courtesy of the National Gallery

of Art, Washington, D. C.

by the Army of the Potomac until March 21, 1863, which proves that this figure was made after this date. In fact, these badges were all important to many children of the period and it became somewhat of a fashion for boys, and some girls, to proudly wear them on their clothes to represent the corps to which their fathers, brothers, and sweethearts belonged. By courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

On August 6, 1861, the United States Congress had passed an act for the seizure of all property used for “insurrectionary purposes,” which was followed by the “second confiscation act” on July 17, 1862. From then on all Confederate property that fell into Union hands would be deemed “contraband of war” and liable to seizure. In effect, even domestic objects fell into this category, including dolls and other playthings. Particularly susceptible to losing their treasured items were those children whose homes stood in the path of General Sherman’s “Bummers” on their “March to the Sea.” In South Carolina for instance, some boys relished the excitement while others, particularly young girls, took note of the atrocity stories and buried their playthings to keep them out of harm’s way. For years after the ending of hostilities children who had faced General Sherman’s soldiers grew up playing at war by hiding their possessions. Nevertheless, some of heir fears were well founded because there were instances of Union troops pilfering dolls and other toys.26 In America since the conflict had begun, numerous youngsters in the United States had sought and collected war relics and had pestered their fathers to send artifacts home. No doubt, amongst the spoils of war some southern toys did find their way northwards, but whether any “contraband” soldier dolls made the trip to Yankeedom we can only surmise, but if so what could have been more iconic in the realms of a Rebel plaything than a rag soldier doll dressed in Confederate gray or butternut brown?

Notes

1. Don Levine and John Michlig, GI Joe: The Story Behind the Legend: An Illustrated History of America’s Greatest Fighting Man, Chronicle Books, San Francisco, Ca., 1996. John Michlig with preface by Don Levine, GI Joe: The Complete story of America’s Favorite Man of Action, Chronicle Books, San Francisco, Ca., 1998. Arthur Ward, Action Figures: From Action Man to Zelda, The Crown Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, England, 2020.

2. Guardian of the Artifacts. Blog 2012. National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

3. The Danville Register, Danville, Virginia, Sunday, April 27, 1969, p. 30.

4. Elizabeth Preston Allen, The Life and Letters of Margaret Junkin Preston, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York, 1903, p. 158.

5. Michael J. McAffe, Zouaves: The First and The Bravest, Thomas Publications, Gettysburg, PA 17325. 1991, pp. 25-26. Frederick P. Todd, American Military Equipage 1851●1872, Vol. II, State Forces, Chatham Square Press, Inc., 1983, p. 751.

6. The Daily Ohio Statesman, Columbus, Ohio, Thursday, October 10, 1861, p. 1.

7. Robin Forsey, The Autoperipatetikos, or Walking Zouave, in Old Toy Soldier, The Journal for Collectors, Vol. 47, No. 2, Summer 2023, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, pp. 27-33. Dorothy S. Coleman, The Collector’s Book of Dolls Clothes: Costume in Miniature 1700-1929, Crown Publishing, Inc., New York, 1975, p. 139.

8. The New York Herald, New York, New York, Sunday, March 5, 1865, p. 8.

9. Ibid., Thursday, July 27, 1865, p. 6.

10. Published under the heading of Comical Sights in New York, this article appeared in The Union and Journal, Biddeford, Maine, Saturday, November 16, 1867, p. 1.

11. Extract from an article entitled The Toy Business in the United States, published by the Manhattan based periodical Scientific American. Apparently this piece was reprinted in several newspapers during its day including The Daily Bee, Sacramento, California, Friday Evening, December 14, 1866, p. 1.

12. Cleveland Daily Leader, Morning Edition, Vol. XIX, No. 275, Cleveland, Ohio, Saturday, November 18, 1865, p. 4.

13. Ruth Painter Randall, Lincoln’s Sons, Little, Brown and Company, Boston and Toronto, 1955, pp. 86-88, 138. Julia Taft Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston, 1931, pp. 132-138.

14. The Springfield Union, Springfield, Massachusetts, Monday Evening, February 12, 1934, p. 12.

15. James Marten, Children for the Union: The War Spirit on the Northern Home Front, Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, Chicago, 2004, pp. 89-92. Frank

16. B. Goodrich, The Tribute Book: A Record of the Munificence, Self-Sacrifice and Patriotism of The American People during the war for the Union, Derby & Miller, New York, 1865, p. 194.

17. Elizabeth Ann Coleman, Fashionable Fair Females: Charitable Dress in Miniature, in Doll News, Vol. 64, No. 3, Spring 2015, Kansas City, Missouri, p. 32.

18. W. A. Thorburn, French Army Regiments and Uniforms from the Revolution to 1870, Arms and Armour Press, Childs Hill, London, 1969, p. 63;

19. John R. Elting and Michael J. McAfee (Editors), Military Uniforms in America Vol. III, Long Endure: The Civil War Period 1852-1867, Presidio Press, Novato, California, 1982, pp. 74-75.

20. Susan Foreman, An American Civil War Era Vivandière, in Doll News, Vol. 69, No. 1, Fall 2019, pp. 60, 63-64.

21. Erwin O. Christensen, Index of American Design, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1950, pp. ix-xvii.

22. Alphaeus H. Albert, Record of American Uniform and Historical Buttons Bicentennial Edition, Boyertown Publishing Co., Boyertown, Pennsylvania, 1976, pp.40-44. Illustrated Catalogue of Arms and Military Goods: Containing Regulations for the Uniform of the Army, Navy, Marine and Revenue Corps of the United States, published by Schuyler, Hartley & Graham, Military Furnishers, 10 Maiden Lane and 22 John Street, New York, 1864, p. 71.

23. Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, The Dyer Publishing Company, Des Moines, Iowa, 1908, pp. 21-38.

24. Susan Bradford Eppes, Through Some Eventful Years, J. W. Burke Company, Macon, Georgia, 1926, p. 253.

25. Edmund L. Drago, Confederate Phoenix: Rebel Children and Their Families in South Carolina, Fordham University Press, New York, 2008, p. 37.

26. Earl Schenck Miers (editor), When the World Ended: The Diary of Emma LeConte, Oxford University Press, New York, 1957, p. 7.

27. James Marten (editor), Children and Youth during the Civil War Era, New York University Press, New York and London, 2012, p. 122. Drago, Confederate Phoenix…” pp. 94, 96.