By 1860 children made up well over a third of the United States population and, for those families who could afford them, commercially made playthings were readily available. As for toy soldiers, “tin-flat,” paper, and wooden figures could all be had. However, when it comes to identifying the manufacturers of the latter type, it is a near impossible task. While considerable numbers of wooden toys were imported from Europe, many were also made in America, but by whom it is difficult to say. Although United States census records and city trade directories can be helpful, as a rule they only listed those companies which referred to themselves as toy makers. Not registered were the numerous individual artisans throughout the country who also made playthings, but on a very localized and often irregular basis by tradesmen such as carpenters and cabinet makers who conducted their business from small workshops. Because their toys often resembled folk-art, little is known about such products or the men who produced them. However, one person whose name has been passed down through the ages is that of Joseph Stuntz, who, together with his wife Appolonia, ran a small fancy goods shop at 375 New York Avenue in Washington, D. C.

Even years after their passing it was said: “Mention Stuntz at any club or dinner or social gathering in Washington and the floodgates of reminiscence are opened. Throughout the dark days of the civil war and reconstruction, in days of national plenty and panic, the little candy shop kept open all day and throughout the evenings to satisfy the wants of children and brighten the lives of fathers and mothers.”1 In fact, it seems that during the Civil War and Reconstruction era, this little store may have been the only one of its type in the city. However, what undoubtedly added to the shop’s fame was that during the Civil War it was often frequented by President Lincoln and his youngest son Tad. During such visits it was said that Mr. Stuntz “would bring forth a box full of the ‘President’s own,’ as he would call a particular regiment of blueclad soldiers, and with these for men and ramparts formed of candy boxes and dolls’ houses, the Chief Executive and his son would lose their worries, real or fancied, in the fascination of the game of ‘playing war’.”2

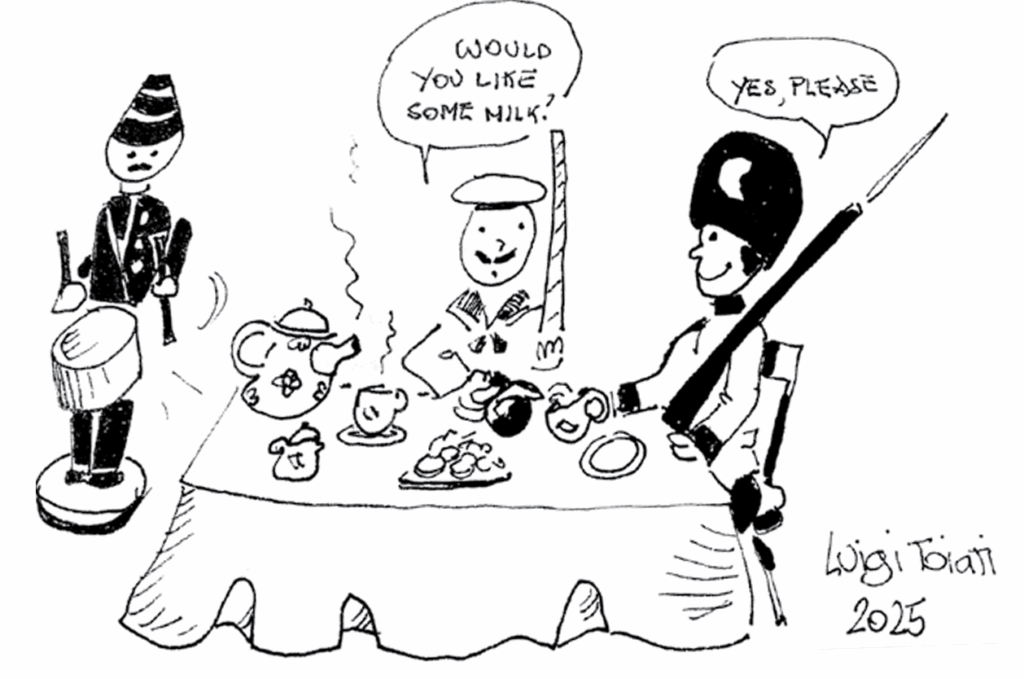

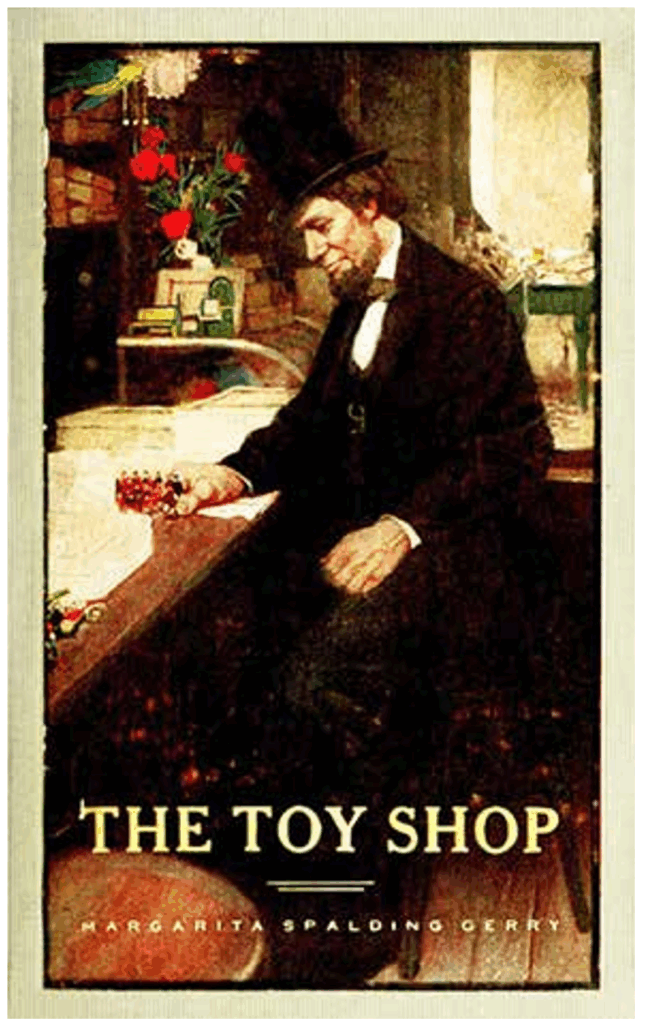

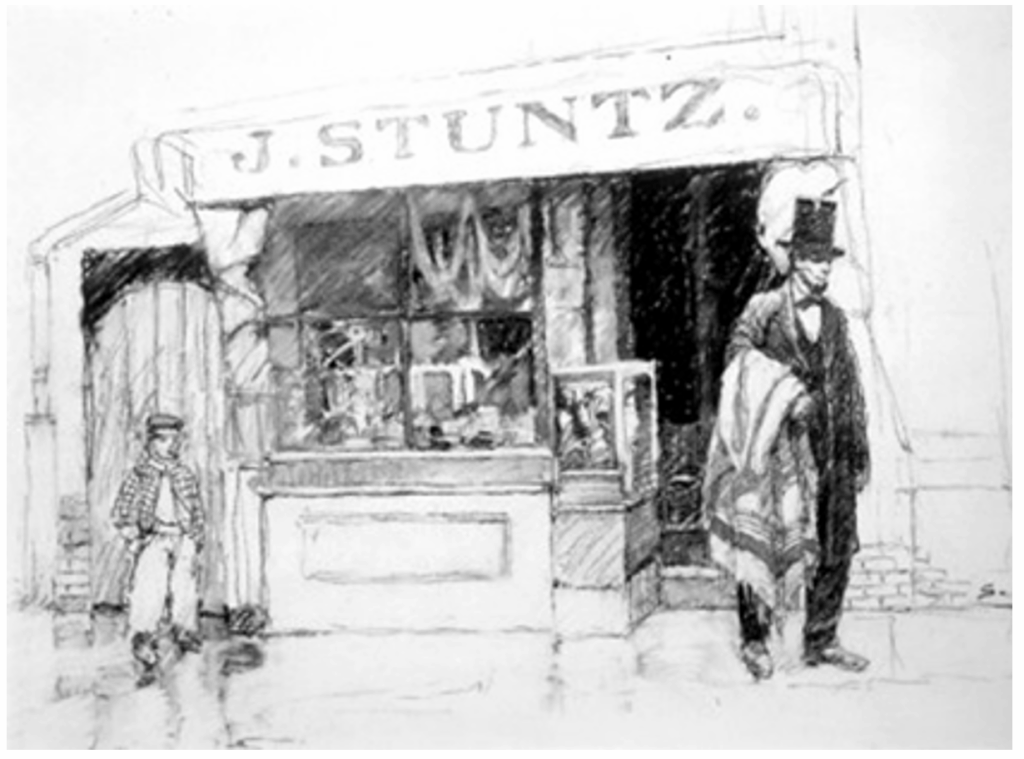

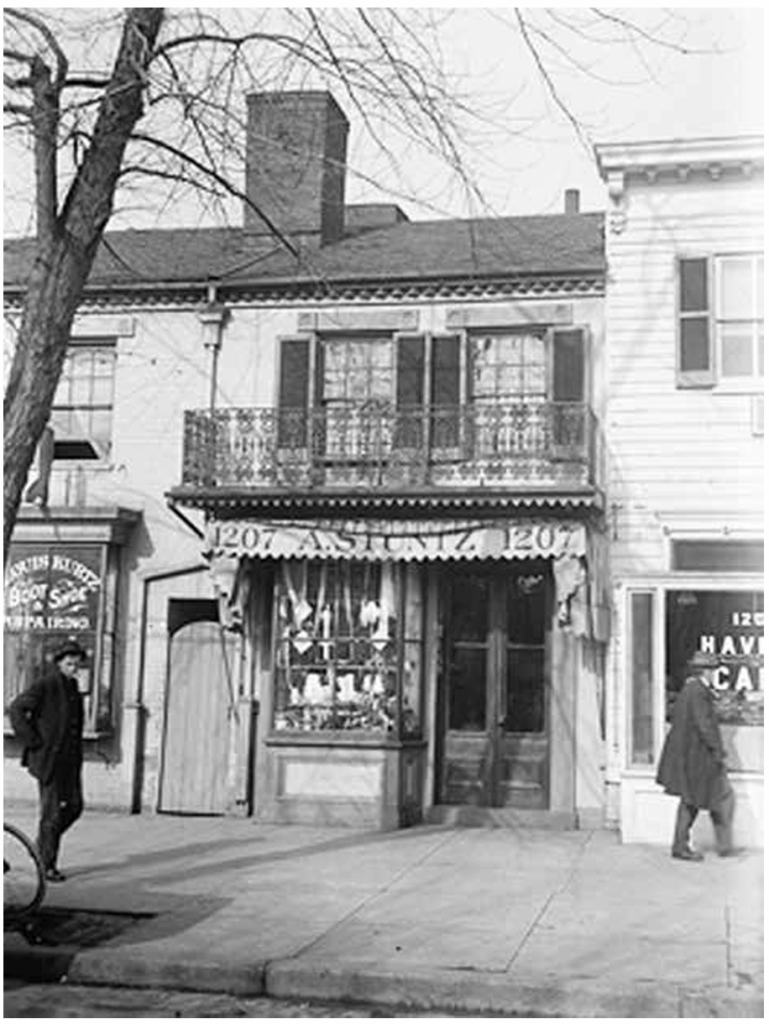

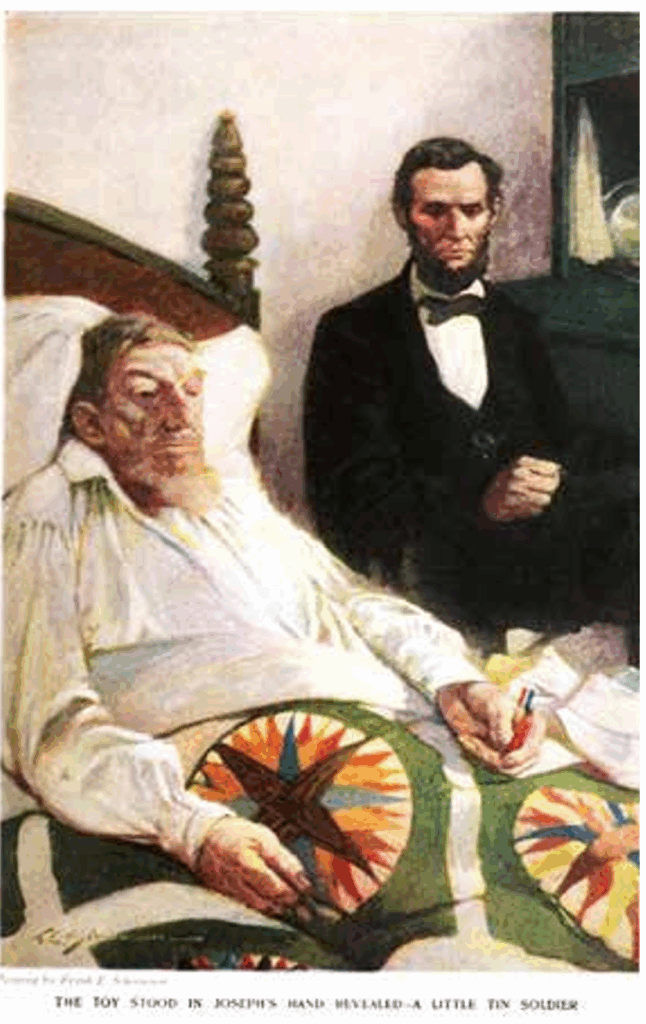

Yet much of the information published regarding Joseph, and in particular the Lincoln visits, was based on aging memories and hearsay. In fact, little had been written about the subject until the author Margarita Spalding Gerry decided to put pen to paper (see Illus. 1). The work which she wrote was entitled The Toy Shop, and with graphics supplied by the renowned artist Frank Earle Schoonover (Illus. 2), it first appeared in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in December 1907.3 During the following year Harper & Brothers deemed her story worthy enough to publish it in book form (see Illus. 3). In the novel Gerry referred to the surname of Joseph and Appolonia as Schotz whereas in reality it was Stuntz. Whether this was intentional or an error on her part is not known. Although classed as a novel it was said: “It is appropriate on the eve of the celebration of the centenary of Lincoln’s birth, that this short story of the war President… should be put into book form for wider reading.”4 However, apart from that used for the front cover, most of Schoonover’s illustrations which accompanied the magazine article were omitted from the book.

Lincoln’s birth, that this short story of the war President… should be put into book form for wider reading.”4 However, apart from that used for the front cover, most of Schoonover’s illustrations which accompanied the magazine article were omitted from the book.

For those who are not familiar of the piece is about a tall dark and sad looking stranger who on a raw December’s day enters the Stuntz fancy goods store to buy toy soldiers for his son. “The little shop was a modest place” and amongst the “homemade candies and cakes” and “a rosy-checked apple or two” were toys, including “little imported German toys”, and “marching valiantly over the shelves, storming wooden boxes flanked with cannon, were toy soldiers. There were, too, all the necessary trappings of combat – swords, guns, soldier suits, arrayed in which youthful generals could marshal their forces and sweep the enemy’s army before them…” Gerry went on to describe the sad looking stranger’s other outings to the shop and how it was not until later that Joseph and his wife discovered the man’s identity. He was none other than the President of the United States!

As for Mr. and Mrs. Stuntz not recognizing the Chief Executive sooner rather than later may have been pure poetic license on Gerry’s part. Nevertheless, this was not the only work written by her on Lincoln. It was said that she had made a special study of the “great president” and in The Toy Shop she portrayed some humble incidents through which he “worked out great projects and developed his own moral point of view” and how the “little warriors” had assisted him “visualize the position of the troops at the front.”5 Although no name was given, but if her novel was to be believed it was in this tiny shop, and after seeing a toy soldier in the form of “a plain steadfast little captain standing to attention with a sword”, where Mr. Lincoln decided to place General Ulysses S. Grant at the head of the Union Army. While this is most unlikely, stranger things have happened in the annals of military history.

Although many of the incidents described by Gerry must have been fictitious, or at least considerably embellished, something must have fired her imagination to write the work. Maybe she was told stories about the President’s visits by the shop’s aging proprietor, Appolonia, and her assistant, “Miss Kate,” both of whom would have been present during the Lincoln forays. Of course, there were also other people who could recall the Chief Executive’s outings. Individuals such as the former slave Elizabeth Keckley, who was Mrs. Mary Todd Lincoln’s dressmaker and chief confidant (see Illus. 4). She remembered that on many an evening she was sent by Mrs. Lincoln “over to the toy shop to tell the President to bring Tad home to his supper…I would find the three of them all wrapped up in the working of some new toy Mr. Stuntz had just gotten from abroad. Mr. Lincoln was as much interested in watching the boy as the boy was in watching the toy. He always sighed when he had to leave.”6

Once Gerry’s story had been published, the flood gates opened and the press were soon printing articles about the small store and the Lincoln incursions. This included visits such as that which supposedly took place during December 1862, just after the Battle of Fredericksburg (in which the Union Army had suffered heavy casualties). Apparently, Tad “amused himself by shooting down little tin soldiers by means of a toy cannon” and seeing “the grim suggestion in the childish play” the President turned to Mr. Stuntz and said: “Does it hurt you as much to have your soldiers shot down as it does me to have mine?”7

Yet another White House regular who sometimes accompanied the President was Thomas Pendal who was a member of the Chief Executive’s personal staff. “Tom Pen” as Tad called him, was a great favorite of the boy and spent that much time with him that he knew better than his father what toys pleased the lad most. Apparently within political circles the fame of the diminutive store was soon secured and it was said “that many a man who wished a favor from the president, bought toys from the Stuntz shop, for little Tad.”8 As for other Lincoln family members who visited the premises, it is possible that prior to his untimely death on February 20, 1862, that Tad’s slightly older brother, “Little Willie,” also crossed the threshold. If so, he may have been accompanied by the eldest of the Lincoln boys, Robert, who towards the end of the war was serving as assistant adjutant on General Grant’s immediate staff.

After “Little Willie’s” passing, evidence does suggest that the President and Tad did become inseparable and undoubtedly one of their popular haunts was the Stuntz shop. Being only about four blocks from the White House, they would slip out of the mansion’s backdoor and could often be seen walking to the little emporium. No doubt, Mr. Lincoln did find its atmosphere relaxing and somewhere where he could temporarily forget his wartime worries and responsibilities. Here, the President and Tad would watch Mr. Stuntz carve his toys and hear stories about serving in Napoleon’s Army, and of travel. Evidently Mr. Lincoln and Stuntz became good friends, and he probably was also one of the shop’s best customers. This is indicated by the recollections of Major Albert E. Johnson who was a secretary to U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. After the President’s assassination the Major recalled that those who were preparing the White House for its new occupants came across an unused upper room full of toys.9 No doubt Mr. Lincoln also bought playthings for other children of whom he was fond. Indeed, it was said that the President was “a lover of children” and “used to hold a monthly reception for the boys and girls in the White House…”10 As for Joseph Stuntz’s toys, apparently “they were of the best manufacture and found a ready market amongst the best families of the National Capital.” Although he carved other playthings, but being an old soldier, we can only assume that his miniature f ighting men were his pride and joy. Besides these, it was said he was also noted for making “batteries of little wooden cannon…”11 But what of his toy soldiers? What did they look like?

Decades ago, when the study of toy soldiers was in its infancy, for guidance researchers had often turned to the superb artwork undertaken by Frank Schoonover to illustrate Margarita Gerry’s novel in Harper’s Monthly. However, being that these pictures did not materialize until 1907, undoubtedly Schoonover based the figures upon those that were readily available during his day, by which time not only were fully rounded lead “solids” commonplace, but even hollow-cast figures had made their debut. However, one author who did not rely on Schoonover’s illustrations was Ruth Painter Randall, an American biographer who specialized in the lives of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln. In her book Lincoln’s Sons she said that Joseph especially did “delight in making little wooden soldiers, officers, and men and their equipment of swords, guns, and cannon. Coming from France, he certainly must have carved and painted perfect miniature Zouaves with their red, blue, and gold uniforms.”12 However, whether he did turn out any Zouaves is debatable. In fact, in her book she made no attempt to depict Joseph’s toy soldiers, and rightfully so. Indeed, it is only since more recent times that we have got a rough idea of what Joseph’s little fighting men probably looked like and this is due to five wooden figures which came up for auction at Christie’s on December 3, 2010 (see Illus. 5). Of course, not being maker marked it is impossible to say with any certainty that these were made by Stuntz, but being handed down by the Lincoln family over the generations, and due to the Lincoln association, it is most likely. So, what do we know about Joseph, the events which lead to him becoming one of America’s early toy soldier makers, and the history of the famous shop where he made them?

He was born on August 10, 1792, in Blundenz in the Tyrol, an Alpine region in Central Europe. Following the defeat of Austria by France in 1805, the area was ceded to Bavaria, which in 1806 became a kingdom in the Confederation of the Rhine; a confederation of Germanic client states established at the behest of Napoleon. Like many others it seems that young Joseph was spellbound by Bonaparte and at the age of twelve he ventured to Paris, where it was said he became apprenticed to “Cadieux,” a cabinetmaker to Napoleon at the Tuileries Palace. No doubt it was due to visions of glory that he joined the French Army, but due to his tender age he was given the position of a standard bearer. While serving in the Russian Campaign of 1812 he was wounded in the foot, an injury that was to plague him for the rest of his life.13 What he did immediately following the demise of Napoleon is not known. It is unlikely that he returned to the Tuileries Palace because, directly after the Emperor’s downfall, its gardens became a large encampment for Russian and Prussian soldiers.14 In fact, dates seem to suggest that it was during the Restoration era of the French monarchy and during the reign of King Louis Philippe that he decided to migrate to the United States.

The earliest record found regarding his activities in America was in the 1842 Philadelphia Directory which listed him as a cabinetmaker at 76 South Front Street. On July 30, 1844, he filed a “Declaration of Intent” with the Philadelphia court system, but evidently a few years would pass before he was to be granted United States citizenship. The last time he was mentioned as being in Philadelphia was in the 1846 Directory when working at 343 Callowhill Street.15 Information regarding his activities after this date becomes somewhat obscure. For instance, at least a couple of early twentieth century press articles tended to suggest that while in Philadelphia he got married, “but the young wife the boy found there died when his baby died, and alone he took to the road again. Mexico allured him and for some years New Orleans knew the skill of the fingers trained in the emperor’s service.”16 However, no record has been found regarding such a marriage in Philadelphia and neither has any information come to light about his activities in Mexico or New Orleans. In fact, if he did practice his woodworking skills in the Crescent City, his stay must have been short lived because by the early 1850s he had surfaced in Maryland.

It was said that Joseph could speak German, French, Spanish and English, and “wanted to work for no less an employer than the government…He came to Annapolis… and began a great order for furniture to be used for ship f itting out at the navy yard of the old state capital.”17 However, what this work actually entailed is unclear because to the best of the writer’s limited knowledge, the only government establishment which was at Annapolis during the period was the United States Naval Academy, established in October 1845. Undoubtedly during this era Joseph must also have ventured to Baltimore. Indeed, it was in Baltimore and at the Alphonsus Roman Catholic Church where he married Appolonia Koch on August 21, 1852. Appolonia had been born on August 15, 1810, in the Bad Durkheim region of the Kingdom of Bavaria and had arrived in the United States around 1840 and maybe with other family members. Undoubtedly, she was not the only member of the Koch family living in America. As for Joseph, the last record found of him being in Baltimore was on June 10, 1856, when he was granted United States nationality at the United States District Court.18

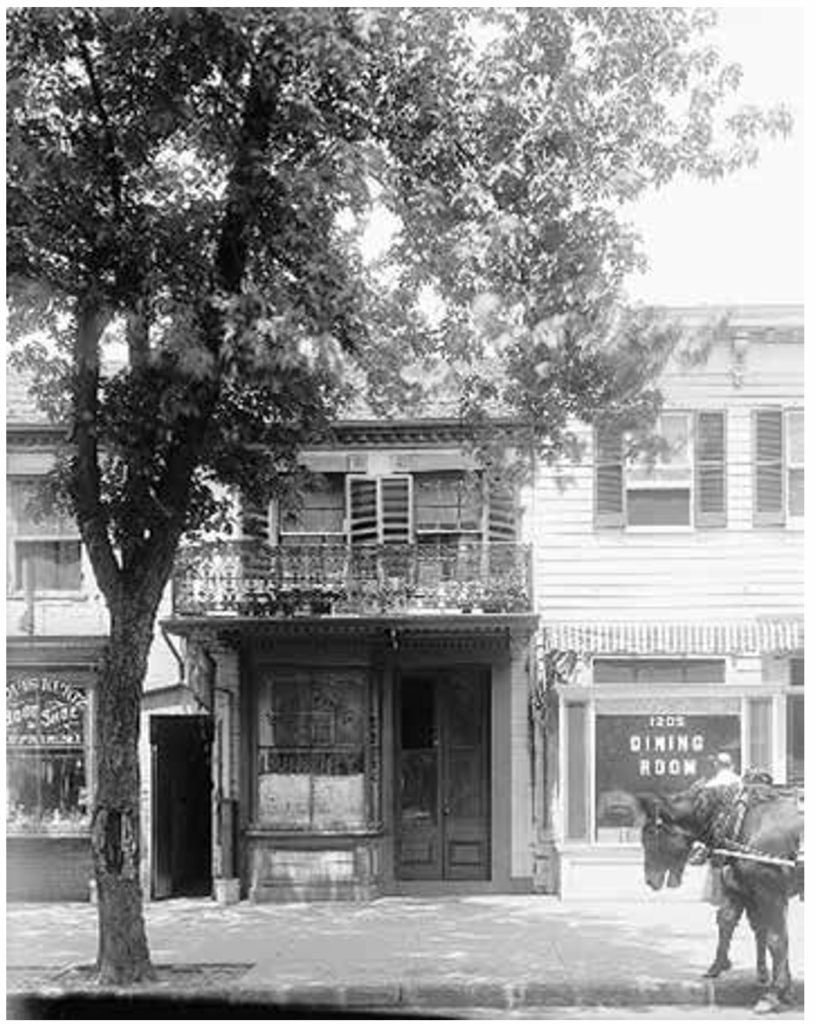

What then followed we can only surmise, but the general consensus of the press was that while working on his ship furnishings Joseph’s old war wound in his foot reopened and unable to continue, he and his wife decided to relocate to Washington. The property which they moved into was 375 New York Avenue. Nevertheless, there is some conflicting evidence as regards when they took up residency. One particular source says that the property was “built by Ulysses Ward, who bought the land on Oct. 14, 1840, for $157…In 1847, Ward leased the place to Joseph and Apolonia (sic) Stuntz…The couple converted it into a shop.”19 If correct, this possibly indicates that where Joseph did work on his ship furnishings was not at Annapolis, but the Washington Navy Yard. However, where this information was gleaned is not known because it most certainly contradicts all other sources. In fact, all the early twentieth century newspapers seemed to have been in agreement that Joseph had “entered Washington in 1855, the same year the Japanese nation…entered into its place among the great nations of the world”, but in Washington the opening of the “Toy shop” was regarded “as the greater event.”20 Yet even this date is open to question. Evidently it was not until around 1860 when the Washington trade directories began listing Joseph and his “dry goods” shop. Of course, not all businesses were immediately included in such publications and by this date the tiny emporium may have been well established. By 1862 the directories were referring to the place as a “fancystore.”21 Built of brick and situated in a row of what once were small dwelling houses, whether Joseph and Appolonia converted the ground floor themselves into a store has not been determined. The shop itself took the form of a long tunnel (see Illus. 6), and next to it was a small back room where Joseph, with his leg propped-up on a stool to relieve the old war wound in his foot, would carve his toys (see Illus. 7). However, making playthings may not have been an entirely new phenomenon for him. Being born and bred in the Tyrol “where forests abound, there the peasants” spent “much of their time in making toys.”22 Maybe Joseph’s family, amongst other carpentry endeavors, had carved toys for a living, and if so, it was in his blood.

Of course, besides playthings the tiny emporium also sold other commodities. While Joseph added to the store’s notoriety with his toys, Appolonia also furthered the shop’s fame with her culinary skills, and it was said that even the North and South united on the matter of her “taffy.”23 She was also a very patient lady and made a specialty of her penny counter for the young ones. On this counter, and besides tasty candies, were numerous small toys. Apparently, it would take hours for those who had wheedled pennies out of their parents to decide how to invest their money. Indeed, taking everything into consideration, it seems that Appolonia may have been the one with the business head on her shoulders. In fact, whether the signage above the premises ever read “J. STUNTZ” (Illus. 8) is open to question because evidence suggests that throughout the store’s existence it displayed “A. STUNTZ” (Illus. 9).

Because the shop was situated in the heart of the residential part of Washington, it seems to have been within walking distance for most. When Joseph and Appolonia had first arrived in the city it was by no means a vibrant place, but all this was to change following the outbreak of hostilities. The loyal states rushed troops to the area and over the next four years many thousands more would follow. The city’s population grew dramatically, and all this began to give Washington an air of Yankee bustle and trade.24

Of course, all this would have had an impact on the tiny shop. Undoubtedly its clientele increased greatly and besides its regular customers, including members of the judiciary and other government departments, it would also have become frequented by visiting army and navy officers and politicians who were eager to buy presents for their little folk back home. Thus, it is possible that some of Joseph’s wooden fighting men found their way far beyond the borders of the District of Columbia. No doubt his woodworking capabilities were unable to keep up with demand because it became “necessary for the wise-managing wife to add to their stock with toys from Baltimore, imported from the old country.”25

Referring back to Gerry’s story, she said that due to Joseph’s deteriorating health he had to take to his bed, which he insisted on being brought downstairs and placed in the back room of the shop. One of the reasons given for this was that he did not want to be “banished from the children’s domain.” He still wished to see the children buying their toys. If Gerry’s novel was to be believed it was whilst bedridden in the back room where he greeted the President for the very last time. The war had drawn to a “victorious conclusion” and the Chief Executive thanked Joseph, saying “you can never know from what you saved me – you and the toy-shop.” The President then handed Joseph a parcel, which contained a toy soldier in the form of a Napoleonic color-bearer. The story implied that Mr. Lincoln had found this little figure in the “conquered city…” (Illus. 10). Of course, the novel ended on a sad note, with news arriving in the shop of the President’s assassination.

Nevertheless, undoubtedly many of the incidents above described were fictitious. Although there was probably an element of truth about Joseph having his bed placed in the back room of the store, but this was probably due to the deteriorating condition of his ancient war wound. He was no longer capable of climbing the stairs. Yet as for him being visited by Mr. Lincoln following the “victorious conclusion” of the war, this must have been pure fiction because by 1865 evidence suggests that Joseph had passed away.

He was buried in Saint Mary’s Catholic Church Cemetery and although the date on his grave reads “April 25, 1867,”26 all other sources suggest that “he died in 1864, before the close of the war…”27 In fact, the date of 1864 is even indicated by browsing through the Washington trade directories.28

No doubt due to his declining health Joseph had not carved any playthings for quite a while, but the fame of the shop continued. Naturally after his death the entire business passed into the capable hands of his loyal wife, Appolonia (Illus. 11). Around 1868-1869 the property was renumbered 1207 New York Avenue, Northwest.29 As in previous years, the little emporium continued to be frequented by noteworthy individuals. It was said that all of President Andrew Johnson’s grandchildren and his twelve-year-old son “knew where to buy toys.” Likewise, the families of President Grant, General Sherman, President Hayes and President Garfield all crossed the threshold.30

Over the years Appolonia had become a personal friend to many of the city’s high society and to oblige her customers she was even prepared to post items to distant parts. Yet despite the celebrity status of her clientele, the little shop never grew opulent or lent itself to the air of a big store, but evidently it always did a brisk business. Indeed, even by 1870 it seems that Appolonia had purchased the property off Ulysses Ward and besides the value of the real estate of two thousand eight hundred dollars, she had also amassed personal assets totaling three thousand dollars.31 Purported to have been the oldest storekeeper in Washington, on April 19, 1901, she passed away. The ensuing funeral procession proceeded from the little shop to St. Mary’s Catholic Church Cemetery, where her remains were interred with those of Joseph’s.32 Maybe this was when the discrepancy emerged as regards to the date of Joseph’s death on the memorial.

In her last will and testament dated August 7, 1889, Appolonia had bequeathed a life interest in her entire estate to her assistant, Miss Kate France, upon whose death everything was then to be sold, and the proceeds go to St. Mary’s Catholic Church. However, her brother, Anthony Koch, contested the will stating that at the time the document was executed his sister was “not of sound mind and capable of making a contract” and it was written “under undue influence of some person or persons unknown.”33 Nevertheless, apparently the case was dismissed because “Miss Kate” did become the shop’s new proprietor (Illus. 12). She had grown up with the business and was probably the “little clerk” who Margarita Spalding Gerry referred to in her story as staring “with mouth open at the big man who played with toys.” This is an incident which supposedly took place during one of the Lincoln visits when the President marshaled huge amounts of toy soldiers and cannon on the shop counter.

Variously referred to as Catherine or Katherine France in official documents, she had been born on March 15, 1850, in Frankfort am Main. The daughter of John and Maria Frantz, the family had migrated from Germany to the United States in 1858 and apparently settled in Washington. Her father may have been the carpenter listed at 377 New York Avenue.34 It is difficult to say what was the relationship between Mrs. Stuntz and Miss France. Undoubtedly “Miss Kate” was more than just an employee. Some press reports indicated that Appolonia was her guardian while others suggested that Appolonia had adopted her.

In 1909 and under Miss France’s tenure it was said that a good deal of attention was paid to the shop “during and directly preceding the celebration of the Lincoln centenary…” In fact, outwardly the tiny emporium had changed little since the Civil War and even the signage above the door continued to read “A. STUNTZ.” Yet the commodities on the shelves did slightly differ. While toys continued to be sold, the passing of Appolonia did spell the end of the culinary delicacies and in their stead were “spools of cotton, tape, darning thread and other notions.” Nevertheless, the Washington notability continued to visit, including the lawyer and politician James Rudolph Garfield whose children “loved the place…” On one occasion he went in to buy toy soldiers, probably for one of his sons, but to his dismay: “Wonderful leaded soldiers were produced,” as they were now made in Germany. Evidently, they were not to his liking because he cried: “Wooden soldiers – I want wooden soldiers that come in a box that I had when I was a boy.”35 However, not being born in Ohio until October 17, 1865, indicates that the wooden soldiers of which he reminisced could not have been made by Joseph Stuntz.

On August 25, 1913, at the age of sixty-three, Miss France died in the apartment above the store “of heart disease, after an illness of several weeks.” Her funeral took place on August 27, and: “Hundreds of children with tear-wet eyes mourned…the passing of Miss Kate, the ‘Toy Lady,’ whose funeral drew them to St. Mary’s Church.” Her remains were interned in the church’s cemetery. She had been associated with the little emporium for over half a century and may have been the last person living who personally witnessed the Lincoln visits and the President’s toy soldier play. While the death of “Miss Kate” did spell the end of the toy shop, the actual building was to survive for another couple of decades.36

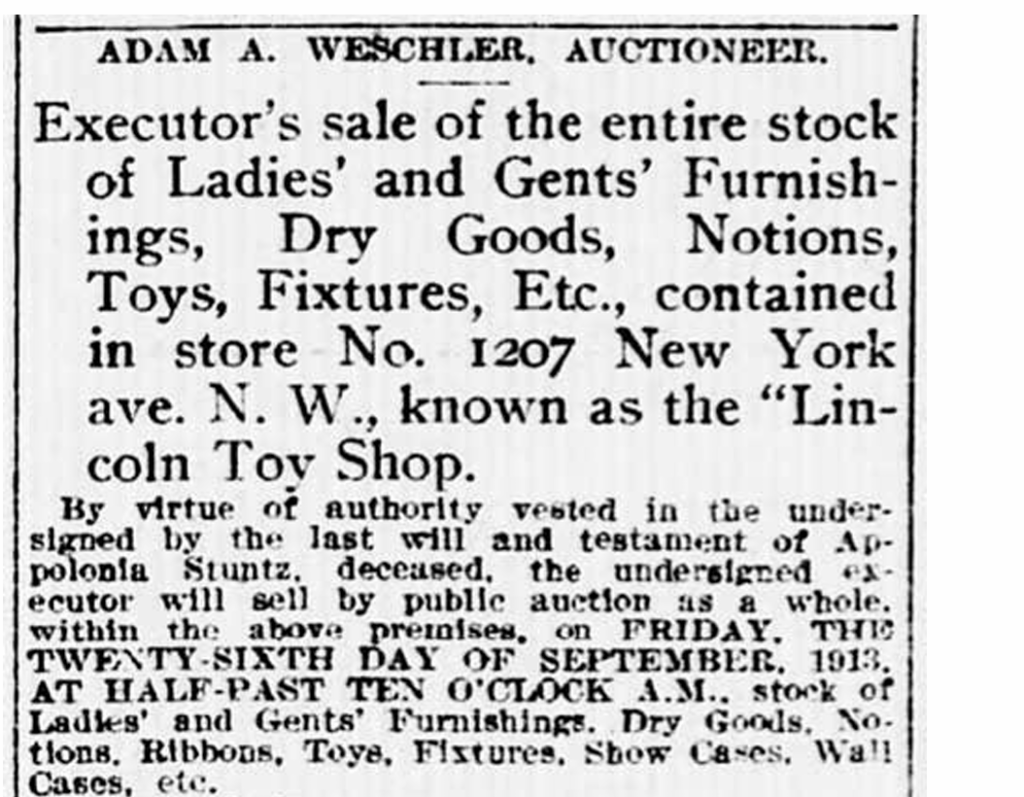

As stipulated in Appolonia Stuntz’s last will and testament, upon the death of Miss France the entire estate was to be sold and the proceeds go to St. Mary’s Catholic Church, but it was rumored that a nephew of Appolonia’s who lived in New Orleans (probably George Koch) was to “contest the instruction.” Nevertheless, on September 26, 1913, the shop’s entire stock, fixtures and f ittings came up for auction – (Illus. 13). Yet the sale could not have been entirely successful because on October 24, an advertisement appeared for merchandise that was still left on the premises (Illus. 14). On November 6, the real-estate itself came up for auction and eventually passed into the hands of Achille E. Burklin, the proprietor of the Lerch cleaning establishment, who paid twelve thousand one hundred dollars for the place.37

By this date the property was in a sorry state and “the only reminders of the days of Lincoln” were dirty and dingy shelving and frayed strips of yellow wallpaper which hung from the ceiling and walls. The plan of the new owner was merely “to remove the traces of age with paint and paper and offer the place for rent.”38 The tenant who took up residency was Lee Lung who ran a Chinese laundry at nearby 1217 New York Avenue. The last time Mr. Lung was recorded as operating from the erstwhile toy shop was in 1919 (Illus. 15). After this the property was used by the Lerch French Dyeing & Cleaning Company, but for just how long is difficult to say because in August 1923, the owner of the firm, Achille E. Burklin, passed away.39 Nevertheless, despite the building’s new found role in the city’s commerce, it still remained somewhat of a tourist attraction and many Washingtonians still continued to refer to the place as “Lincoln’s Toy Shop.” Yet even during its heyday the store was never officially called a “Toy Shop,” let alone “Lincoln’s Toy Shop.”

Since around 1912 rumors had been afoot that the property was to be demolished, and the area redeveloped. The end finally came in November 1933, when the structure was torn down. On December 6, certain members of the Association of Oldest Inhabitants of the District of Columbia held a meeting and during the proceedings a Mr. Proctor presented them with “an old brick from the front wall of the Lincoln Toy Shop…”40 Just how many similar relics have survived, if any, is not known, but what could better to supplement any collection of Civil War era playthings than a souvenir from Lincoln’s Toy Shop?

Notes

- The Wilson Echo, Wilson, Kansas, Thursday, March 11, 1909, p. 4.

- The Washington Herald, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, November 9, 1913, p. 5.

- Margarita Spalding Gerry, The Toy-Shop, in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, Vol. CXVI, No. DCXCI, December 1907, Harper and Brothers, New York City, pp. 3-15.

- The Evening Star Part 3, Washington, District of Columbia, Saturday, December 19, 1908, p. 6.

- The Springfield Leader, Springfield, Missouri, Tuesday. November 19, 1907, p. 3; The Topeka Daily State Journal, Topeka, Kansas, Saturday, December 7, 1912, p. 15.

- The Washington Times, Washington, District of Columbia, Monday, September 2, 1912, p. 6. Although the press referred to “Elizabeth Kechley (sic)” as “a maid”, she was actually Mary Todd Lincoln’s seamstress and chief confidant.

- Greeley County Republican, Tribune, Kansas, Friday, February 11, 1910, p. 1.

- Ibid., also Fall River Globe, Fall River, Massachusetts, Saturday, March 23, 1918, p. 7.

- The Sunday Star, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, December 22, 1907, p. 51.

- The Springfield Union, Springfield, Massachusetts, Monday Evening, February 12, 1934, p. 12.

- The Times, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, April 21, 1901, p. 7; The Sunday Star, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, December 27, 1914, p. 48.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Lincoln’s Sons, Little, Brown & Company Ltd., Boston and Toronto, 1955, p. 180.

- The Sunday Star, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, November 26, 1933, p. 75; Fall River Daily Globe, Fall River, Massachusetts, Saturday, March 23, 1918, p. 7.

- Emmanuel Jacquin, Les Tuileries, Du Louvre á la Concorde, Editions du Patrimoine, Centres des Monuments Nationaux, Paris, 2000, pp. 24-27.

- See Joseph Stuntz in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S., Naturalization Records, 1789-1880, and the Pennsylvania and New Jersey, U.S., Church and Town Records, 1669-2013. Of all the A. M’Elroy’s Philadelphia Directories checked from 1820 to 1858, Joseph Stuntz only appeared in those for 1842 (p. 260) and 1846 (p. 349).

- The Detroit Free Press, Detroit, Michigan, Sunday, December 22, 1907, p. 56; The Sunday Star, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, December 22, 1907, p. 51.

- Ibid.

- See Apollinia (sic) Koch in 1852 Baltimore Roman Catholic Parish Marriages, Park Avenue & Saratoga Street, Maryland, United States, and Joseph Stuntz in the U.S. Naturalization Records Indexes 17941880.

- https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2003/dec/19/20031219-07 Toy store brightens Lincoln’s dark days. The bedrock for this online article, was a piece which originally appeared in the Washington Times on December 19, 2003. However, where the person who wrote the article obtained his information is unclear. Undoubtedly it contradicts many other sources.

- All newspapers of the day which reported on the issue were in agreement that Joseph Stuntz had “entered Washington in 1855…” The quote cited here is from The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, Missouri, Sunday, December 22, 1907, p. 25.

- Boyd’s Washington and Georgetown Directory, compiled by William H. Boyd, Washington, D.C., 1860, p. 258, and that of 1862, p. 166. Other Washington directories checked by the writer were for the years 1846, 1850, 1853, 1855, and 1858.

- Weekly Patriot and Union, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Thursday, August 17, 1865, p. 3.

- The Detroit Free Press, Detroit, Michigan, Sunday, December 22, 1907, p. 56.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington 1860-1865, Harper & Brothers, New York and London, 1941, pp. 83-84.

- The Detroit Free Press, Sunday, December 22, 1907, p. 56.

- See Joseph Stuntz in the U.S. Find a Grave Index, 1600s-Current.

- Several newspapers of the early twentieth century were in agreement that Joseph Stuntz had died in 1864. That quoted is from The Inola Register, Inola, Oklahoma, Thursday, January 21, 1909, p. 3.

- See Boyd’s Washington and Georgetown Directories, 1864 (p. 258), 1866 (p. 368), 1867 (p. 535). 1868 (p. 421).

- Boyd’s Directory of Washington and Georgetown, 1869, p. 268.

- The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, Missouri, Sunday, December 22, 1907, p. 25.

- See Appoloniea (sic) Stuntz in the 1870 United States Federal Census.

- The Times, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, April 21, 1901, p. 7. See also Appolonia Stuntz in the U.S., Find a Grave Index, 1600-Current.

- The Times, Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 1901, p. 8; Ibid., Saturday, May 25, 1901, p. 2; The Evening Times, Washington, District of Columbia, Saturday, May 25, 1901, p. 6; The Times, Wednesday, June 19, 1901, p. 8.

- See Catharine (sic) France, U.S. Census 1900, Washington, D.C. The Washington Times, Washington, District of Columbia, Tuesday, August 26, 1913, p. 7. See also various documents under the names of John Frantz, Maria Frantz, and Rhinhold France at Ancestry.com

- The Sunday Star, Washington, Sunday, December 27, 1914, p. 48, Ibid., Sunday, December 22, 1907, p. 51.

- The Washington Times, Tuesday, August 26, 1913, p. 7; The Evening Star, Washington, District of Columbia, Wednesday, August 27, 1913, p. 16; The Sun, Baltimore, Maryland, Thursday, August 28, 1913, p. 5.

- The Washington Times, Tuesday, August 26, 1913, p. 7; The Evening Star, Washington, Monday, September 22, 1913, p. 16; Ibid., Friday, October 24, 1913, p. 18; Ibid., Saturday, November 1, 1913, p. 18; The Washington Herald, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, November 9, 1913, p. 5; The Washington Post, Washington, District of Columbia, Sunday, December 7, 1913, p. 3.

- The Washington Herald, November 9, 1913, p. 5.

- Various issues from 1913 to 1923 of Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia. For information on the Lerch French Dyeing & Cleaning Company and the death of Achille E. Burklin see the Evening Star, Washington, Monday, August 20, 1923, p. 7; Ibid., Thursday, August 13, 1925, p. 10.

- Ibid., Thursday, December 7, 1933, p. A-12.